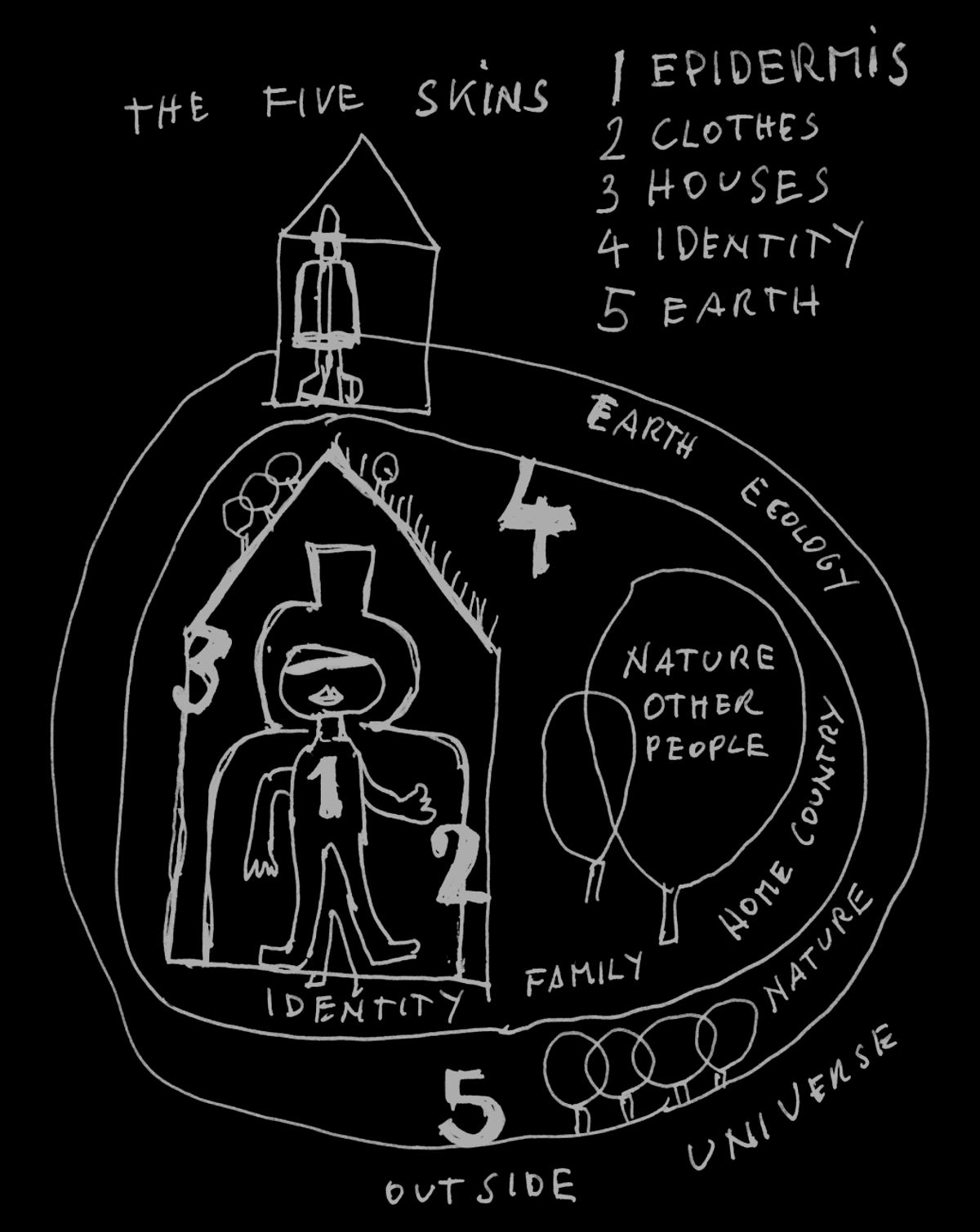

The Painter King with the Five Skins

Five Skins

Conceived for the book The Power of Art, Hundertwasser — The Painter-King with the Five Skins by Pierre Restany, published by TASCHEN in Cologne in 1998.

For Hundertwasser, man has three skins: his natural epidermis, his clothes, his house. When in 1967 and 1968 the artist delivered his naked address to proclaim man’s right to his third skin (the free alteration of his house), he accomplished the ritual full cycle of his spiral. He re-found his first skin, that of his original truth, his nakedness as a man and painter, by stripping off his second skin (his clothes) to proclaim the right to his third skin (his home). Later, after 1972, when the major ideological turning-point had been passed, the spiral of Hundertwasser’s chief concerns began to unfold. His consciousness of being was enriched by new questions, which called for fresh responses and elicited new commitments. So appeared the new skins that were to be added to the concentric envelopment of the three previous ones. Man’s fourth skin is the social environment (of family and nation, via the elective affinities of friendship). The fifth skin is the planetary skin, directly concerned with the fate of the biosphere, the quality of the air we breathe, and the state of the earth’s crust that shelters and feeds us.

Pierre Restany — The Power of Art. Hundertwasser, The Painter-King with the Five Skins, Cologne: Taschen, 1998, pp. 10/11.

The First Skin

Hundertwasser believed each individual was responsible for nurturing their creative spirit. He encouraged people to fight the “new illiteracy” — the inability to create.

The first skin – the epidermis – goes through constant change and growth, just as human beings undergo constant growth and development. The first skin symbolises identity, a person’s right to her or his own needs.

Commenting on his Japanese woodcut ‘Right to Create’, Hundertwasser said

Our real illiteracy is not the incapability to read and write but the incapability to create. The children and the so-called primitives and the so-called fools have a bigger knowledge to create until they lose their soul by uniformation, education and convention.

The Second Skin

Clothing is forever, just like art. Clothing must become art again and stop being just fashion.

In 1949, Hundertwasser was travelling through Italy when he met the French artist René Brô, who amazed him with his peculiar clothing style. Inspired, Hundertwasser began making trousers and shoes for himself; later he designed clothes and caps to be sewn, and pullovers and socks knitted. He became a forerunner of the Creative Clothings Movement.

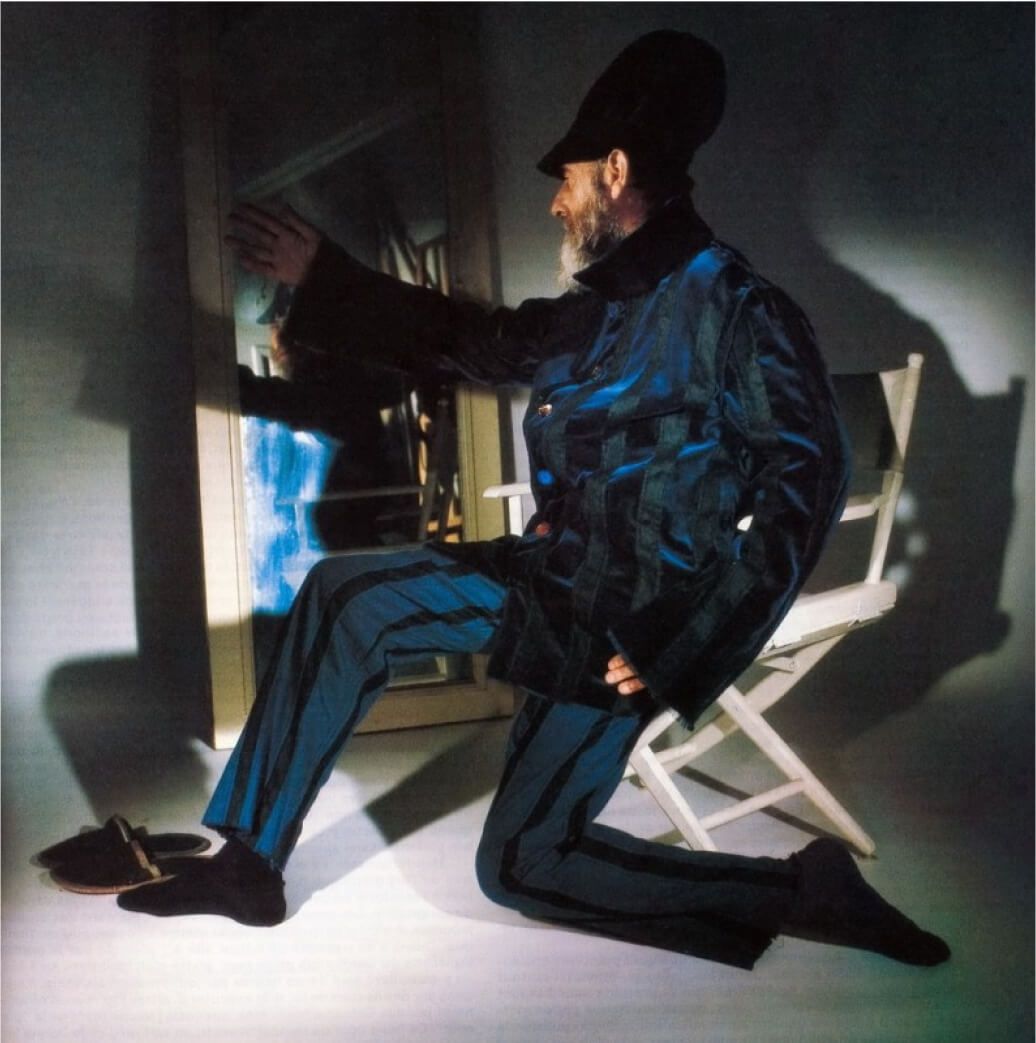

In 1982 the French edition of Vogue invited Hundertwasser to design a suit and write about fashion for the magazine. He summarised his ideas in the manifesto “On the Second Skin” (1982/1983), where he railed against conformity, fashion and clothing that’s anonymous, average and symmetrical.

If the Second Skin is taken ill or is made uniform or is not in keeping with man, doesn’t befit man, then man, i. e., the organism situated beneath it, will also get sick. And that is one of the main reasons why our civilisation today is sick...

Finished-part production and factory-made garments are removing us farther and farther from the creative design of our own clothing, which is not just something which one wears on the outside. For clothes make the man. That is not just a proverb, that’s a fact, the truth. 1982

The Third Skin

Clothing and buildings have undergone a development in the past centuries that no longer correspond to nature and the needs of the individual.

When Hundertwasser delivered his Speeches in the nude for the Right to a Third Skin in Munich in 1967 and Vienna in 1968, these were seminal moments. He had shed his Second Skin (his clothes) to reclaim his original truth as a painter and man (his First Skin) and advocate for the Third Skin (architecture).

Hundertwasser was protesting against the geometrical straight line, the grid system and rationalism in architecture, and for a person’s right to freely alter their own house. He didn’t hold back when it came to the lack of creativity and imagination in most architecture.

When I look outside, I see that everything is full of ruled and T-squared misery and everybody is imprisoned… We live in buildings which are criminal and which were built by architects who are really criminals… Architecture should not start growing until people move in and not vice versa.

1967

Hundertwasser realised more than 30 architectural projects around the world in which there are window rights for the tenants, uneven floors, green roofs, tree tenants and spontaneous vegetation. As an architect, Hundertwasser put diversity before monotony, believing in each individual’s right to alter their homes and express their creativity.

The Fourth Skin

Our identities are based on differing from each other. Identity for Hundertwasser was an important quality. Each human being is identifying with a specific group or nation. Hundertwasser created many distinctive signs of identity, designing stamps for Austria and other countries, and flags for New Zealand, Australia and East Timor, as well as a flag to symbolise reconciliation between the Jewish and Arab peoples.

These creations were just as colourful and individual as his paintings. By expressing his protest against artistic, political and social standardisation, he hoped to inspire others.

He was also firmly against the idea of the European Union.

The so-called E.U. is contriving to destroy our life base, our age-old cultures, our small, evolved idiosyncrasies, our species diversity and our self-esteem… The E.U. countries are being reduced to the lowest common denominator, rendered anonymous and robbed of their identity.

1988-1994

The Fifth Skin

We must make a peace treaty with nature.

Hundertwasser believed that nature is the only superior creative power on which humanity depends. His respect for nature aroused in him the desire to protect it against the attacks made on it by people. This is the fifth skin: ecology and mankind.

At a time when the green movement was first coming into being, he went to work on the preservation of our natural surroundings, promoting a life in harmony with the laws of nature. He campaigned on many ecological issues: against nuclear energy, for the saving of oceans and whales, for tree planting and afforestation of the cities, for rainforest protection, and for using public transport instead of private cars, and more.

Hundertwasser’s property in the Bay of Islands was one of the places where he put many of his ideas about living in harmony with nature into practice. He planted thousands of trees, had houses with grass roofs, used the humus toilet, had solar panels and refined his system of purifying water using aquatic plants.

If man walks in nature’s midst, then he is nature’s guest and must learn to behave as a well-brought-up guest.

(Hundertwasser in a 1976 interview with art critic and author Pierre Restany.)