Hundertwasser in New Zealand 1973 - 2000

Exhibition

Hundertwasser Art Centre presents Hundertwasser’s artistic legacy in New Zealand, 1973-2000, in an exhibition of artworks curated by the Hundertwasser Foundation in Vienna.

The exhibition includes original paintings, graphic works, tapestries, applied art, original posters and architectural models.

Paintings

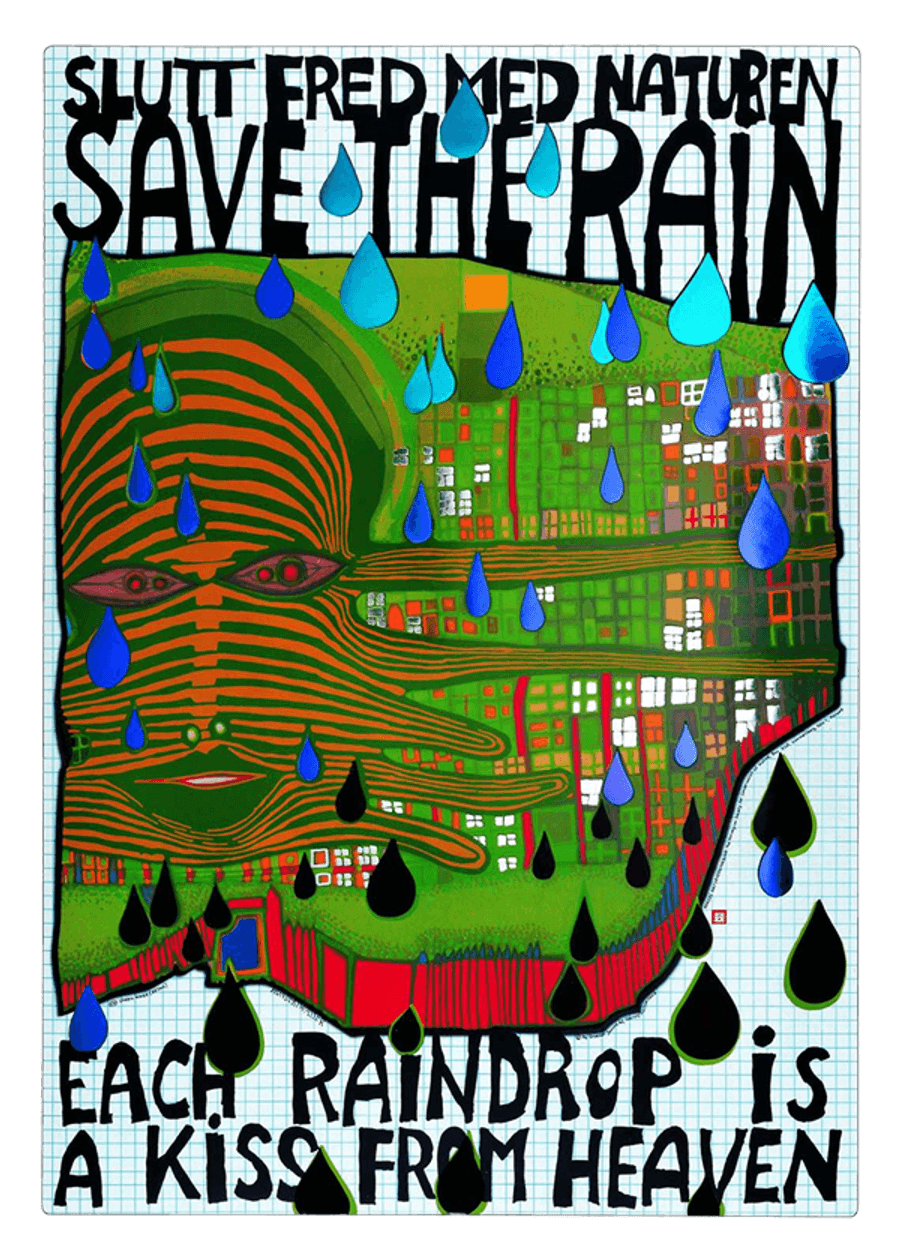

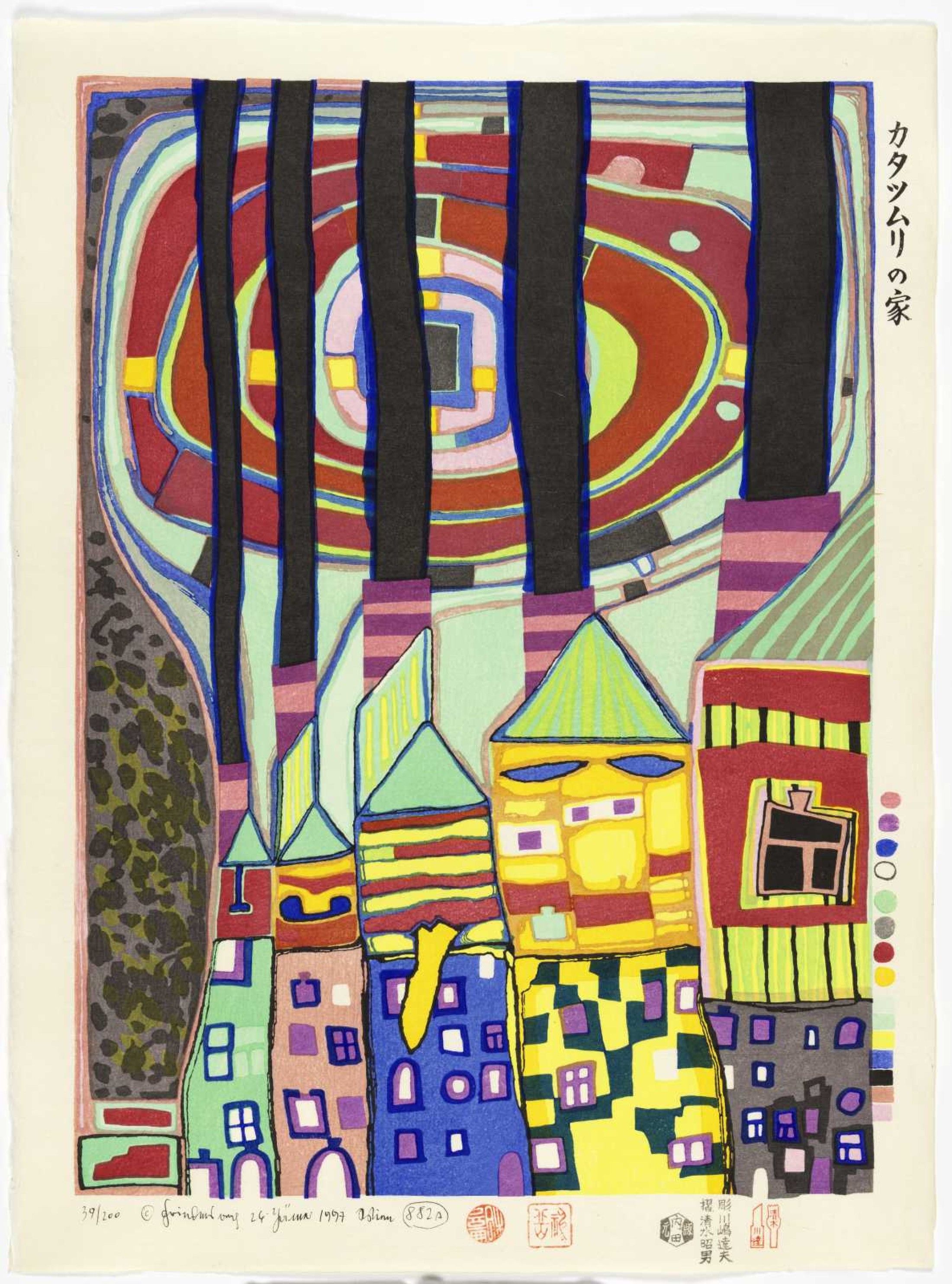

Hundertwasser’s paintings are instantly recognisable, due to his idiosyncratic, energetic style and his exuberant, visionary use of colour. Although he was influenced as a young man by the Jugendstil, particularly the works of his fellow Austrian Egon Schiele, Hundertwasser moved beyond these modernist beginnings to develop a unique visual language of his own, as well as a repertoire of motifs that connect his painting to his personal philosophy. Hundertwasser rejected the modernist drive towards essentialism and simplification of forms in favour of a maximalist approach that celebrates baroque, decorative intricacy. Typical subjects include biomorphic, fantastic cityscapes, faces, ships, landscapes, trees and water, often in the form of rain or teardrops. Non-representational motifs such as spirals, concentric circles or stripes occur throughout the work, as do organic, deliberately imperfect checkerboard patterns that playfully manifest the artist’s disdain for grids, right angles and mechanically straight lines.

Technically, Hundertwasser’s painted output is highly accessible and democratic in nature. His artmaking practice was something he carried with him on his travels, and was seldom confined to a studio environment. Early in his career, Hundertwasser often worked on found materials such as paper or cardboard, rather than traditional canvases, reflecting his resourcefulness and an interest in the aesthetic qualities of unconventional materials. He made use of a wide range of media, including watercolours, charcoal, chalk, egg tempera, oil paint, shellac and gold leaf. This emphasis on spontaneity and fluid approach to materials parallels Hundertwasser’s desire to see art and architecture liberated from the academic confines of the studio and reintegrated into the fabric of the everyday. He also expressed an admiration for the art of children, which he viewed as an authentic expression of the creative impulse, freed from the shackles of cultural orthodoxy.

Despite his exuberant aesthetic and loose, organic approach to composition, Hundertwasser’s use of his materials was careful and deliberate.The paint is very often laid down in thin, transparent layers, creating a sense of depth and a jewel-like intensity of colour. His paintings tend to consist of evenly applied cells or facets, giving them a characteristic stained-glass appearance. His work is never chaotic or overtly expressive in terms of paint handling, with few visible brushstrokes and a general sense of orderly process. Despite this, his painting remained largely intuitive, reflecting his concept of “trans-automatism,” by which he meant a blending of conscious and unconscious impulses into one flowing outpouring of artistic activity.

Graphic Works

From the outset, graphic works were an important part of Hundertwasser’s practice. In terms of technique, Hundertwasser’s graphic works have many features in common with the rest of his pictorial output. As in the paintings, the picture plane is broken up into clearly delineated areas, with an emphasis on line and colour. A noteworthy early example of his graphic work was a lithographic portfolio produced in association with the Vienna Art Club in 1951 on a commercial rotaprint machine, with the intention of creating cheap, affordable graphic art that everyday people could afford. This portfolio consisted of nine prints in a limited colour palette of black, red, blue and green. Even at this early stage, it was clear that print was a medium that suited Hundertwasser’s methodical style and his interest in line and figuration. Another important event in the evolution of Hundertwasser’s graphic works was his time spent painting and exhibiting in Japan in the early 1960s, during which he developed an interest in traditional ukiyo-e Japanese woodcut printing. Like lithography, ukiyo-e had traditionally been an accessible, mass-market medium, although one conducted on a pre-industrial basis. Very unusually for a Westerner, Hundertwasser would go on to produce Japanese woodcut prints himself, working with traditional Japanese craftsmen to translate his designs into print.

Over the decades, Hundertwasser would continue to develop and extend his graphic practice, creating ever more elaborate and intricately constructed works. For example, the 1983 print 10002 Nights Homo Humus Come Va How Do You Do was printed using four separate lithographic colour separation layers, with an additional eight screen-printed and stamped layers added on top. As the title implies, this work was printed in an edition of 10,002 signed copies, each of which had a different combination of colours. This massive undertaking highlights the extent of Hundertwasser’s commitment to the medium, as well as underscoring an apparent dichotomy at the heart of his printmaking practice, namely how to square his desire to democratise art and make it accessible to everyday people with his distaste for mass produced items.

Architecture

Although it is perhaps his largest and most visible legacy as a creative practitioner, Hundertwasser’s architecture is best seen as an extension and continuation of his painting, artistic philosophy and environmentalism. His engagement with the architecture of cities began very early in his creative life. In a 1993 interview with Harry Rand, he cites as an important influence the way Egon Schiele painted buildings, commenting that “For me, the houses of Schiele were living beings. For the first time, I felt that the outside walls were skins.” This sense of viewing architecture through the lens of painting permeated Hundertwasser’s approach, bringing an improvisational freshness and a willingness to question orthodoxy to what has traditionally been among the most conservative of creative endeavours.

Hundertwasser’s desire to build seems to have stemmed from a sense of injustice and a self-imposed mission to cure what he viewed as the sick status of the modernist city. The architectural designs he created are a natural extension of his own “transautomatic” aesthetic sensibilities: hand-drawn organic lines rather than ruler-straight ones, variety and heterodoxy rather than uniformity. Tiles, onion domes, and roof afforestation replace pitched or flat housetop designs, while windows come in a multitude of shapes and sizes, deliberately breaking the grid structure inherent to modernist architectural practice. Often, buildings are oriented horizontally rather than vertically and, where possible, they are integrated into the surrounding environment, bringing nature into the fabric of the structure through “tree tenants” and vertical greening.

As a way of realising his vision for architecture, Hundertwasser began by constructing models in the 1970s, before beginning to work on the modification of existing structures in the early ‘80s. Ultimately, he would start to see his designs realised as full-scale building projects as the decade progressed, as was the case with the Hundertwasser House in Vienna, which began construction in 1983. Although he had been writing and lecturing about architecture since the late 1950s, it was not until the ‘80s that even the most innovative clients were ready to implement his ideas about sustainability and environmentalism, at the risk of criticism from the mainstream. However, in the long term it is fair to say that, rather than changing to suit the times, all Hundertwasser needed to do was wait until they caught up to him.

Ecology

Perhaps as impactful as his artistic achievements were Hundertwasser’s efforts as an advocate for environmentalist causes. As the decades passed, Hundertwasser’s advocacy for technologies such as compost toilets, plant-based water purification and recycling systems passed from being fringe ideas to finding mainstream acceptance. So too did his strong anti-nuclear stance, his advocacy for the preservation of wetlands and rainforests and his opposition to the overuse of pesticides and antibiotics.

As evidenced by his numerous manifestos and lectures on the topic, Hundertwasser’s creative practice was inextricable from his ecologically conscious philosophy. For Hundertwasser, environmentalism was not a pragmatic or goal-oriented choice, but a question of ethics. He viewed nature as an ultimate good, in and of itself, and believed that making the natural world a part of the domestic, everyday experience was a necessary correction of moral wrongs wrought by the industrial revolution. Hundertwasser was also a believer in the autonomy of the individual, and had faith that given the opportunity, people would choose what was best for themselves and for nature. His ecological stance was also, in this sense, a justification of the value of creativity and artistic expression as a means to heal the self, the home and the ecosystem sustaining them.

As well as lending his voice and personal support to the environmentalist movement, Hundertwasser also produced numerous poster editions, the proceeds from which were used to promote the causes depicted. His architecture, too, was meant as a demonstration of the value of putting his ecological ideas into practice; projects such as his 1974-5 model for a “green motorway,” recessed below the ground to disperse noise and lined with tree plantings to absorb exhaust, feel as fresh and timely today as they did when they were first proposed.

Indeed, Hundertwasser’s reconfiguration of the industrialised European city as an Edenic, utopian garden-space feels increasingly timely and relevant as the fragility of the natural world, and humanity’s massive impact on it, become ever more apparent.

Andrew Clark 2021